The Internet & Trauma are Built by the Same Architect.

I read this Substack post just before, and it brought to the surface something I have been thinking about myd entire life.

I genuinely think the concept and unpacking I’m about to do this, will be significantly helpful in the framing of how your brain is operating in the digital landscape, and how that contrasts with physical reality.

This is the essay I read, it is by Katherine Dee, who I have been enjoying reading the work of.

The Medium is the Monster

I think it can definitely be read first, but isn’t necessary in order to understand and unpack what I’m going to write about.

I was reading it when I got to this line:

“In 2014 in Waukesha Wisconsin, twelve year old Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser took their friend and classmate, Payton Leutner, to a nearby woods and stabbed her 19 times. They claimed they did this to become proxies, or acolytes, for the Slender Man. The stabbing signalled the end of the “golden era” of Creepypasta and sparked a familiar moral panic around what media children can access on screens unsupervised.

The investigation and trial following “the Waukesha Slender Man Stabbing” revealed that Geyser suffered with early-onset childhood schizophrenia, and both she and Weier were found not guilty by mental disease or defect. Geyser remains committed to a forensic psychiatric hospital while Weier remains under supervised release, her Internet usage strictly monitored with no use of any form of social media. Following the attack, the Waukesha Police Chief warned parents that the Internet is “full of dark and wicked things” that lurk to drive children to stab their friends at the behest of fiction and narrative.”

I cannot describe the intensity of which I gagged reading this. I almost threw up.

Specifically, it was when I read that one of the Slender Man attackers was diagnosed with early-onset schizophrenia. Because, I know what that means in a way I wish I didn't.

Before the internet, a person with schizophrenia hallucinated in ways that were culturally bound. A child in the 1970s might see demons, ghosts, religious figures—because these were the dominant narratives of their environment.

Even in 2006, when I was dating someone with schizophrenia, and the years following, they hallucinated with things that had been experienced, were tangible and I could visualise.

But a person with schizophrenia in 2024?

Their hallucinations are trained on infinite, algorithmically-generated horror.

They are hallucinating inside the internet.

The images that flood their mind are not personal, not regional, not tied to history or culture. They are flashes of memes, creepypasta, stitched-together viral imagery—horror distilled into its most fragmented, free-floating, contextless form.

I know that my ex, now heavily reliant on therapeutic Ketamine to keep him from hurting himself or anyone around him, would fall to one million pieces if locked in a room with only the Internet. There simply would be no boundary or rationality to understand whether what you were seeing was real or not and at a certain point, it simply doesn’t matter, you are just - reacting.

The Slender Man stabbing was not an isolated case. It was a precedent.

A moment when a fictional narrative became boundary less, and bled into ontological reality. There is no flattening, its just a stitching.

What happens when you take a brain that is already prone to splitting and place it inside a system that does nothing but split, pattern-seek, and reconstruct alternate realities?

What happens when there is no longer a distinction between hallucination and content?

You can see why I wanted to vomit.

I have spent years trying to articulate the way trauma rewires the brain—not just emotionally, but structurally, computationally. It is not simply about intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, or emotional dysregulation. It is a fundamental rewiring of cognitive function. And the more I have studied, the more I have lived inside my own mind and the more I learn about myself now that I am well and truly sober, the more it becomes apparent to me why I am now building software, playing more computer games, and writing like if I stop I may die.

It is a fundamental misunderstanding of everyone researching trauma and pathological gaming that it is about community seeking. It is not. It is about a mirroring of the way your brain functions in an environment that is controlled, so you are actually able of forming any kind of connection that resembles what people consider to be “normal” or “healthy”.

My brain, my CPTSD brain, games and the internet all operate on the same logic.

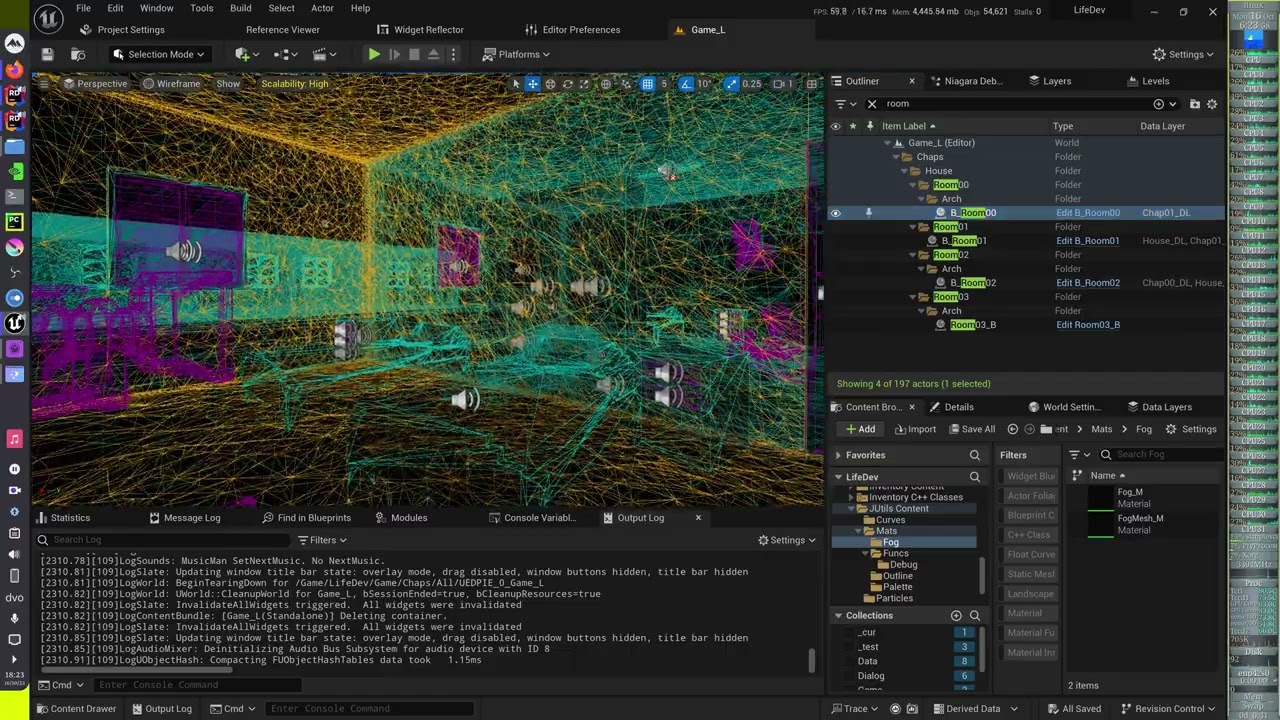

This is a still from a person who builds games to cope with their CPTSD. This is a pretty accurate insight into what my mind feels like at all times.

If you have experienced trauma, especially complex trauma that unfolds over years, your brain stops processing the world in linear narratives. It does not move cleanly from past to present to future. When I was in my late teens and early twenties, I could not differentiate whether I had experienced something yesterday, years ago, or if it hadn't happened at all.

Consequently I became a compulsive liar, in order to ground myself in what was an increasingly crumbling reality. This is one of the reasons I am truly and very uniquely creative, but it is also one of the reasons that I have had so much trouble navigating the world and resorted to alcohol, developed eating disorders and inevitably tried to commit suicide repeatedly over the course of my life.

These outlets become extreme, immediate interruptions that shut off your trauma-struck brain, because the world around you defies your biological logic that was reassembled in order to keep you alive.

When your brain becomes a hyperlinked system of triggers, associations, and recursive loops, a single sensory input—a smell, a sound, a phrase—does not lead to a singular memory. It pulls up an entire category of connected experiences, collapsing time and space into a single, overwhelming flash. Trauma reorganises memory storage. It prioritises patterns over sequence. It prioritises survival over coherence.

One of the simplest ways I can articulate this in a way that people will see the way I describe wine (I am a sommelier for the three strangers that follow me here) is never through linear, structured tasting notes, but rather an abstract cherry-picking from an imaginary constellation of hyper-specific and related examples of things that have even the thinnest thread of relatability between them, and I weave them together to articulate what a wine feels like to me, because this is the only way I know how.

People think it is poetry, beautiful, fun, often pretentious, but for me, it is because my brain is a network that is fuelled by an extraordinary amount of electricity allocated to me being able to observe the world at a level of focus that no one, no one who doesn’t have trauma, could possibly understand.

The closest people get?

Hallucinatory drugs or temporary psychosis from stress, or, from the inevitable deterioration of your mental faculties, when your brain is shooting electricity randomly, not in the predictive fashion it is originally designed to.

When I take drugs that make me hallucinate, it feels normal. When I am at hyper levels of stress, I am rational, serene and composed.

However, I also am high risk for detachment during hallucinations, and the come down for me, is an agonising onslaught of my neurological wiring that genuinely makes me feel insane and completely unmoored. This is why I cannot drink, and I cannot take drugs anymore - it genuinely affects me differently than it does you.

A pre-trauma or never trauma-afflicted brain experiences events, creates thoughts and tells stories in a straight line. A happened, then B, then C. The past stays in the past, the present is the present, and the future unfolds step by step.

My brain does not work this way.

It does not experience time as a sequence. It experiences time as a network. A single moment does not live neatly in the past. It is always accessible, always active, always one wrong click away. I can look at something and be on a completely different plane within my own chronology, and have a trained understanding that I am also in the present and need to understand the two in order to not completely fall apart.

This is exactly how the internet retrieves information. There is no “past” or “present” online. A post from 2009 can be as immediate as a post from five seconds ago. A single search query can surface decades of history in an instant. The internet collapses time in the same way trauma collapses time.

A CPTSD brain does not process past events as over. The past is always running in the background, waiting for the right input to make it front and center again.

The same way a single keyword search can bring up years of digital archives, a single sensory trigger can bring up years of trauma. Both systems obliterate linear chronology.

Trauma memories are not recalled, they are relived. They do not stay confined to their chronological place in your life; they emerge suddenly, without warning, triggered by an association you did not even realise existed. It is completely, utterly unhinged and bizarre.

I love it for the way it makes me describe thing, like wine, like the world, how it processes the art and books and music that I love, but on the other side of that circle is the asme kind of intense and unpredictable, but coupled with the levelled frequency of dark.

This is also exactly how algorithmic feeds function. The infinite scroll never ends. The system is always scanning, always optimising, always categorising content to predict what comes next. You are never meant to reach the bottom of the page.

A CPTSD brain and an algorithm both assume that stopping is dangerous. Both believe that missing information is a potential threat. Both prioritise constant vigilance over rest. And in both cases, this is not a choice—it is a survival mechanism.

One of the most defining characteristics of trauma cognition that mimics an algorithm or predictive model in AI, is pattern-seeking.

The brain, having been hurt in ways it cannot afford to be hurt again, becomes obsessed with detecting signs of future harm.

It is constantly asking:

Have I seen this before? Does this situation resemble past danger? What micro-patterns can I detect that might indicate I am at risk?

It is doing this as fast as any AI we could possibly build. I know I am faster than ChatGPT in this way. The internet operates on the exact same premise. Machine learning algorithms function by recognising patterns in user behaviour, predicting outcomes based on past inputs, sorting information into meaning clusters.

A trauma brain and an AI system both operate on predictive models. Both are designed to assume that every input contains crucial, high-stakes meaning. A casual conversation might not be casual at all—it could be a test, a prelude to harm, a hidden repetition of something painful. Nothing is neutral, nothing is random. This is how a trauma brain stays alive. This is also how the internet keeps you engaged.

And in both cases, this is exhausting. I have to ask “what is happening” to myself after pretty much every interaction I could possibly have because I HAVE to go through all of the options before my brain will let me unclench.

I have never, ever been "entertained" by the internet, this "soothing" effect is because my mind is structured to accomodate spirals and fractures, all cross-referenced upon layers and layers of recursion. The internet is soothing to me, because to me it is a version of rest, one where my brain doesn’t have to accomodate the oppositional logic of the world outside of me.

It is a den of computational logic that my mind can sleep in.

My teenage years were spent inside the process of trauma rewiring—that slow, relentless restructuring of the brain in response to something it cannot fully process. It is beyond efficiently studied these reconnections your brain makes, and even now if I concentrate, I can feel the amount of electricity I generate to think the way that I do.

A trauma-rewired brain does not know how to stop thinking. It is constantly scanning, constantly assessing, constantly looping through every possible interpretation of a moment to prevent danger. Even in moments of supposed stillness, the mind is still processing, categorising, predicting.

This is why hypervigilance exists. Hypervigilance is not just an emotional state. It is a full cognitive reprogramming that tells the brain: never stop scanning for threats. Never stop indexing past experiences in case they are relevant. Never trust that what you see is the whole picture.

People with CPTSD often describe themselves as feeling like they do not have a single, stable self. Instead, they feel like they are a composite of different versions of themselves, activated by different contexts, a collection of conflicting identities, each shaped by different traumas, roles, and survival tactics.

A person who does not fully exist in a unified way.

This is precisely how online identity functions. This is precisely why the person I am on the Internet, in chat rooms, games, anywhere, there is simply for me no pressure to “make a me up”, because I feel made up as it is.

There is no singular self online.

There is only the self presented on social media, the self in private messages, the self shaped by algorithmic engagement, the self that exists as archived posts, ghost traces of previous opinions, versions of you frozen in time.

For me, I have no singular self in reality or the digital, and so I cannot experience what others do in the online world compared to the physical. They may as well be the same, they’re not, but it simply is not within my mental capacity to comprehend otherwise.

I cannot explain the feeling to you when I am playing something like Baldur’s Gate 3. I imagine it is the feeling that people have when they do not have a trauma-wired brain and they are out enjoying their life or sitting in the park with their friends. It is where I feel the most normal. It’s not to say I don’t get immeasurable and nourishing and life sustaining enjoyment from the park with friends, but it is this consistent, reliable and completely impenetrable sense of safety that I have within the framework of a games architecture and narrative that cannot be mimicked outside of a digital realm.

Where I can explain this a little further, is that a CPTSD brain and the internet both create identity through fragmentation. Both are built on the premise that there is no single, stable “I.”

If you have spent your entire life inside trauma rewiring, this feels normal. If you have spent your entire life online, this feels normal.

When I was a teenager, I used to stand in front of my mirror staring at my face, trying to recognise myself. I could not. I could not recognise myself. Still, when I recall people, I do not “see” them, but I see the patterns and the repetitions of them, and I pull them together to construct an image I can begin to trust. If you wonder why I have not recognised you, it is not because I am rude, it is simply because - I do not recognise you.

I have believed I am other people so completely, that I become them. I can make up stories so quickly and so strongly, because I am inhabiting them.

Where this becomes terrifying for me, is that I have learnt to live with this. Just.

Only recently am I in a place where I am happy, secure, gentle, kind. But I see people around me experiencing the things that I have my entire life, but in a way that is simulated, forced, not through re-wiring, but a forced conditioning or mimicry of the way my brain works and it honestly doesn’t surprise me the more and more people around me say they are “in a simulation” because if I was experiencing what they are, in the way they are experiencing what happened to me, I would never, ever of been able to get through it.

There is no such thing as a pre-internet mind anymore. There is no such thing as a generation that will grow up with a singular, linear sense of self. For them, there will be no difference between memory and archive, between cognition and algorithm, between self and feed. They are being raised inside a cognitive model that mimics trauma rewiring without ever having experienced trauma. You may call this age we’re living in one of unavoidable trauma - but that is false.

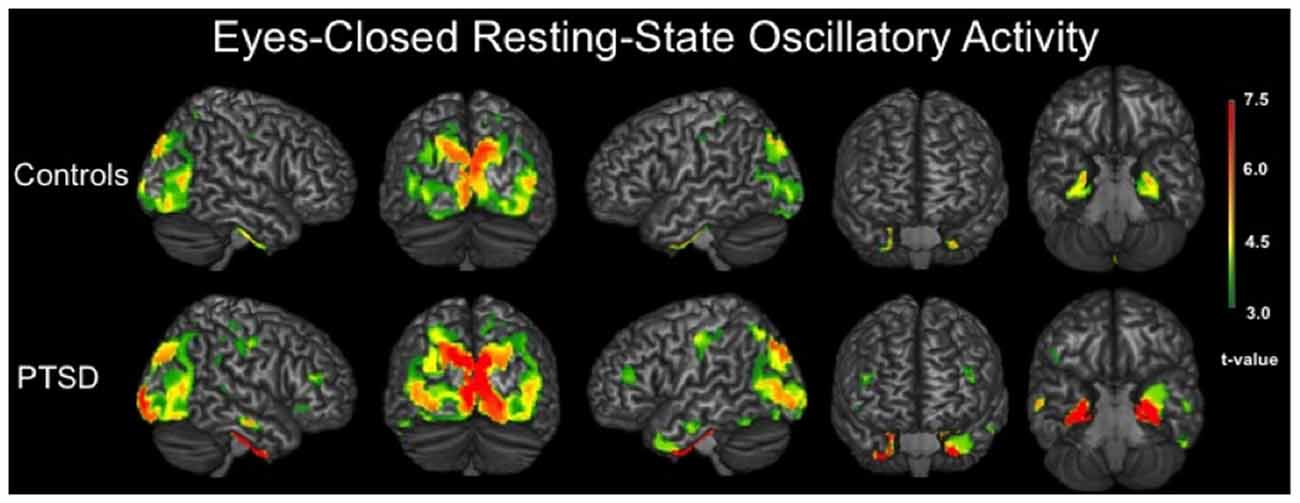

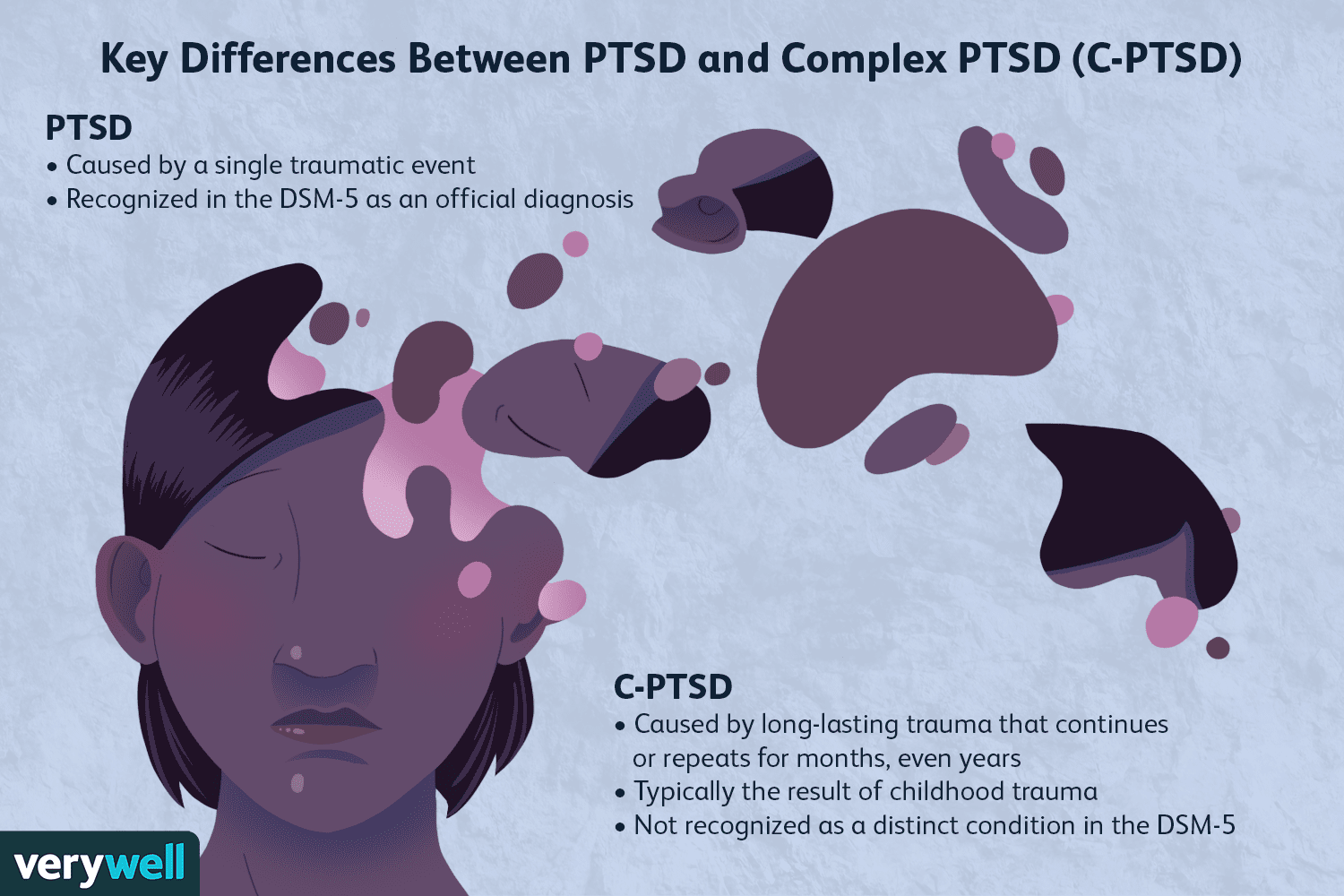

CPTSD affects around a maximum of 4% of the population globally. PTSD is an entirely separate phenomenon, and not to be confused. This affects around the same percentage of people.

What 100% of the population is this dissociation, depersonalisation and de-reality that is one of the symptoms of trauma-rewiring, but without their brains having the infrastructure to support it. It shouldn’t work, and it doesn’t, and that is what is happening to you, and everyone around you. It is impossible not to feel lost because of it.

This is to exist in a permanently untethered state. There is no rejecting of reality, because they simply have not experienced it in a way that we have studied it before. Wee have no idea what this will do to the future of human cognition.

I believe we need to start talking about the internet not as a medium, but as a neurological condition. It has already changed how we process time, structure memory, construct identity.

If you have CPTSD, you already know what this feels like. If you have spent too much time online, you already know what this feels like. The difference is—for us, this was a response to something.

For Gen Alpha, it is the starting condition.

People say Gen Alpha is worse. That they are the most nihilistic generation we have ever seen. I agree that something is happening. But it is not nihilism.

Nihilism suggests a conscious rejection of meaning, an active disengagement from reality. But what is happening here is not a choice. It is not defiance or apathy. It is something else entirely—something more fluid, more automatic, something embedded in the very structure of their cognition before they even had the opportunity to form an opinion about it.

Gen Alpha does not reject reality. They do not choose to disengage. They have never known a world that was not structured this way. Unlike previous generations who experienced the transition into a fully networked existence, Gen Alpha was born into it.

There is no "before" for them. No memory of a time when the physical world held primacy over the digital, when conversations weren’t immediately archived, when the feed didn’t feel like an extension of one’s own consciousness. They do not toggle between online and offline in the way we might perceive it. The separation has collapsed entirely.

Emotional intelligence, as most people understand it, is designed for a brain that was never forced to prioritise survival over connection.

For a trauma brain, the typical frameworks of emotional intelligence—openness, vulnerability, reciprocal trust—are nonsensical. They do not exist as instincts; they exist as threats. When being open once led to violation, when trust led to betrayal, your brain rewires itself to eliminate those risks entirely. So I had to train myself into a version of emotional intelligence that worked within the architecture of my mind, rather than against it. It was not intuitive; it was built, calibrated, and maintained through years of deliberate work.

Now, it is one of the most beautiful things about me—not a natural trait, but a discipline, an ongoing act of care for both myself and others. This is why drinking was so catastrophic for me: it wiped away that maintenance. It reset me back to the core functionality of my trauma brain, where there is no threshold for self-awareness, no space for emotional regulation—just raw, unchecked survival instincts.

And you see this across the board with trauma survivors: emotional intelligence is not an innate trait we lean on, but something we hold up with both hands, every single day.

For Gen Alpha, emotional intelligence will not be something inherited through natural socialization—it will have to be something actively taught, maintained, and contextualised within a world that does not organically reinforce it.

They are growing up in an environment where emotional responses are flattened into reactions, where selfhood is curated like a digital storefront, and where connection is mediated by engagement rather than presence.

The structures that once helped develop emotional intelligence—face-to-face interaction, unfiltered social feedback, the slow, messy process of learning emotional nuance through real-world trial and error—are being replaced by algorithmic validation, performance-based identity, and an overwhelming amount of emotional information with no clear framework for processing it.

If a trauma brain struggles with emotional intelligence because it was taught that vulnerability leads to harm, then Gen Alpha’s challenge is that they are being taught vulnerability is simply inefficient—that emotions are content, that identity is adaptable to the most rewarded form, that the line between sincerity and performance is irrelevant.

Their emotional intelligence will not be absent, but it will be structurally different—more externalised, more patterned, more influenced by mass feedback loops than by deep individual introspection. The question is not whether they will be emotionally intelligent, but what kind of emotional intelligence they will develop—and whether it will be something they can sustain, or something that sustains them.

They are the first generation raised entirely inside the cognitive architecture of the internet. Their reality has always been algorithmically mediated, always filtered through an ever-changing series of digital interfaces.

They do not "go online" because there is no such thing as "offline." The digital world does not sit parallel to their physical world—it overlays it, informs it, seeps into it until the distinction is meaningless. What we once called "real life" is now simply one part of a much larger, much more fluid existence.

Going offline would be the same as your partner going temporarily missing and then suddenly reappearing four days later, with simply no acknowledgement or explanation. That is the gravity of the feeling that Gen Z and Alpha are experiencing with their relationship to digital worlds.

For them, there is no bifurcation between the physical world and the online world. There is no “real” world. There is only the stream. Everything is content, everything is processed through the logic of virality, everything exists in fragments, stitched together by algorithms that dictate what is seen, what is engaged with, what is remembered.

And when all of experience is filtered through a system that prioritizes engagement over depth, performance over presence, spectacle over substance, the nature of perception itself begins to shift.

And this is why I push back against the idea that this is nihilism. Nihilism implies rejection, a conscious turning away from meaning, a decision to believe in nothing. But what is happening here is not rejection—it is dissociation. It is displacement. It is a fundamental rewiring of what meaning even is.

When meaning itself is algorithmically assigned, when emotions are flattened into reactions, when identity is something that must be curated and maintained like a digital storefront, the relationship between self and world begins to fragment in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Gen Alpha is not detached from reality because they refuse to engage with it. They are detached because they have never experienced it in the way previous generations did.

When they say their parents do not understand them, it is true, their parents do NOT understand them.

Their cognition was formed in an environment where reality is not a fixed, stable entity but something fluid, shaped by the logic of the feed. They do not remember a world before attention was a commodity, before every thought and action was shaped by an invisible audience, before existence itself became gamified.

Their minds were formed inside an infinite, liquid, always-on feed, a space where history collapses into an endless present, where context is optional, where the difference between reality and performance is no longer clear. And we have no idea what kind of cognition this is going to produce long-term.

It’s one of the biggest misunderstandings about this generation’s relationship with meaning. They aren’t rejecting meaning; they are floating in an environment where meaning is assigned externally, context is fluid, and there is no clear way to anchor anything.

Meaning isn’t gone—it’s just unstable. And that instability, more than anything else, is what creates the overwhelming, dissociative effect they are describing the only way they know how.

One of the most crucial shifts happening right now is the prioritisation of the external as the primary source of meaning. When identity, memory, and reality itself are structured by engagement, performance, and algorithmic validation, meaning is no longer something internally cultivated—it is something assigned externally, something proven through visibility, something that exists only insofar as it is witnessed and acknowledged.

The inability to recognise this shift, especially across generations, creates a growing chasm of misunderstanding. If you tell someone whose entire framework of selfhood has been shaped by digital existence that their world isn’t real, that their experiences don’t count, that meaning can only be derived from the physical, you are not pulling them back into reality—you are severing them from the only reality that has ever made sense to them.

And what happens when people feel unrecognised, invalidated, and unanchored?

They crowd into the few spaces where their experience is reflected back at them. The more they are dismissed, the deeper they burrow into places where detachment, depersonalisation, and perpetual disconnection are normalised.

I did this in chat rooms as a teen, I did this by binge drinking with anyone I could find, I have pinned parts of my reality to groups, to situations, to things, because it was the only thing that kept me from being completely untethered from the reality I was expected to operate within, but simply was not wired to.

I know when I read stories about Incels, about school shooters, about anything where someone isolated and then catalysed has gone and completely unmoored themselves from time and consequence, I know what it feels like to acknowledge that capacity in yourself as a person - it is true of everyone - but unimaginable to most.

This is how hyper-isolated, hyper-online communities form—not because people reject physical reality, but because the physical world has already rejected them. There is no reason why digital existence cannot be just as meaningful, just as structurally sound, just as real as physical existence.

The danger isn’t in allowing digital spaces to hold weight—it is in trying to suppress or dismiss them, in forcing people into deeper and deeper enclaves of disconnection simply because their experience does not align with a past that no longer exists.

The greater risk is not in acknowledging the validity of digital life, but in ignoring the fact that, for an increasing number of people, there is no meaningful distinction between the digital and the real at all.

I cannot reiterate how important it is, not to associate what people are experiencing as trauma, it is not trauma. It is the re-wiring process happening on the outside, whilst you are processing it on the inside. CPTSD, is the outside encroaching on your inner distortion.

The difference is unbelievably important in understanding how to operate in this context, and even more important to protect those with CPTSD from sourcing the correct treatment and care.

If this is the reality we are living in—if we are witnessing the first generation to develop cognition entirely inside an externalised, algorithmic, fragmented framework—then what matters most is not resisting it, not mourning a world that no longer exists, but understanding how to exist within it without losing ourselves entirely.

This is not about saving Gen Alpha from nihilism; they are not nihilists. This is about understanding that meaning, as we once knew it, has changed. That coherence, as we once experienced it, has changed.

That selfhood, as we once constructed it, has changed. The mistake would be to insist that the past model of human cognition is the only correct one. The mistake would be to assume that what is happening is purely a loss, and not a shift into something else—something we are only just beginning to perceive.

But what cannot be lost in this process is care. The way forward cannot be detachment, cannot be letting people disappear further into isolated, unmoored cognitive states where meaning is so fluid it dissolves entirely. What we need now is a new form of anchoring—not a regression to pre-digital cognition, but an understanding of what stability looks like inside a system that does not naturally provide it.

And that means a new kind of literacy. A literacy not just of information, but of selfhood. A literacy that teaches people how to process meaning in a world where meaning is no longer fixed, how to hold onto identity in a world where identity is algorithmically splintered, how to exist without being consumed.

Because this is not about whether we think the internet is good or bad. It is here. It is structural. It has rewired everything. And if we don’t develop the tools to help people navigate this shift, they will keep drowning in it. Drown like I did for most of my adult life.

They will keep retreating into the darkest, most disconnected places available. They will not get the chance that I did, through career choices that prioritised human connection, living in spaces that required me to engage with the natural world and an intuitiveness and sensory seeking body that understood the difference between kind input and frightening input.

No, they will keep mistaking the feeling of being unmoored for a lack of meaning itself.

This isn’t about saving anyone from the internet. It’s about making sure they don’t disappear inside it.