You will not see the red herring, and it will rot in your hands.

TL:DR

If you share other people’s pain on Instagram, you are responsible for all that follows it.

There was a period of my life—half a decade, probably more—where I became a kind of signpost for other people’s pain. It wasn’t official, but many people I do not know other than through introduction as followers of my Instagram, have said they are grateful for my voice, or acknowledge my presence as safe. This is not a brag, it is a misinterpretation of my having experienced harm, and being able to express it clearly enough when I witness it, so that others may safely digest it themselves.

I have worked in the hospitality advocacy space, and now I do not, but still uphold the behaviour that aligns with this label. I have received hundreds of stories of harm, of violation, of abuse and of the fallout in my Instagram messages over the years, and many, many more in conversation out in the world. Mostly from hospitality workers, but really it has been anyone who has witnessed me and interpreted it as such.

At first I thought I was helping. I thought that listening was a kind of care. I was someone you could message at 2 a.m. I knew what to say. I knew how to reply. I could stay calm, measured, coherent.

Because I have written about harm, and because I’ve stood still long enough to look like a container, they send me a message. They are asking me - what am I holding that you can help me see?

Through filtration of these messages, through knowledge and accumulation, you think you’re absorbing others pain like water through cloth.

But over time something else happens. The stories collapsed. They stopped feeling distinct. Every new message wasn’t new—it was part of the pattern. My brain, already shaped by complex trauma, started to fold the edges of each event into a map. Every venue had a pin. Every person a flag. The patterns weren’t just familiar—they were inescapable.

And it’s not because they’re unoriginal that they become the same. It’s because my brain, already patterned by trauma, starts meshing the data because it correlates. It builds maps. It indexes. It prepares.

And that’s when I realised something no one tells you about being "the person who helps":

You’re not really helping.

You’re witnessing for safety. You are scanning the shape of harm not to feel it, not to heal it, but to understand its architecture. To prove to your brain that it can be predicted. To create an illusion of logic, so that the body doesn’t spiral into collapse.

People thought I was sympathetic. And I am. But that wasn’t the primary function. What I was doing was marking contours.

What I want to say is this: I was never listening because I was generous. I am generous, but the listening does not make me so.

I was listening because I needed to know. I needed to learn how harm sounded, how it unfolded, how people justified it and how they recovered. I needed to know exactly, precisely, where my harm fit within this framework. Because that, that is how trauma works.

Every story I heard became part of a larger system—a mental architecture of risk and recognition.

This is what it looks like.

This is what it sounds like.

This is where it starts.

This is the angle the hand moves.

This is the gap in the door.

This is what they say afterward.

This is where it becomes addictive. When I was a teenager, shortly after I was raped, I started obsessively reading horror movie plots on the back of videos in Blockbuster. I would find as many as I could, reference the pictures, and understand that this was a “type of harm or horror” that was possible. This is categorised as “scary” and this is what it entails. Now I have registered it, I will know when I need to run away.

I must remember this so I know when I encounter it.

I still do this, now on Wikipedia, and when I am, I know I am not feeling good, or I am experiencing something in my life that is causing me stress. An unfamiliar pressure that signals; you must find more information to recognise what this pressure is, where it comes from, and prepare for the imperceivable consequences.

On Instagram, when you are getting a consistent response from an act, a CPTSD wired brain interprets that as a reliable source of pattern encountering. And so, you invite it. If it feels “bad” still, you know you are still sane. The measurement becomes how bad, why is it bad, how long after does it feel bad, how does this person feel about it comparatively?

There is only so much the body can bear as no one is wired to cope with the amount of content that is presented to them on the internet, trauma-wired or otherwise. However, I can speak for the response that it has on a trauma-wired brain in the sense that as the pattern seeking is innate, and instilled in order to keep you alive, you believe it to be as important as drinking water or feeding yourself.

What is the same of all people is cognitive fatigue, or overload, but in CPTSD, it is accompanied by the collapse of suddenly, pattern seeking has harmed you, even your wiring is unsafe, and so you dissociate, hallucinate, try to die, cut, envelope.

Because when your nervous system rewires to track harm, to flatten stories into pattern recognition, it doesn’t just collapse your memory—it collapses your sense of difference. Every new story is the same story. Every violation is part of one long, endless, recursive loop.

That’s why I recognise what I saw in this Instagram carousel, of which I have posted some pictures below. Not the stories themselves. But the logic. The collapsing. The blurring of types of pain into one coherent shape—designed not to witness, but to contain.

I am curious to know what these images stir in you, but I will describe how it makes me feel, and the structure of digital care as I understand it, going forward.

There’s a particular kind of harm that doesn’t arrive as pain, or even as a tear, or a stitch loosening—it arrives as form. As the shape something takes when it tries to be understood.

You feel it when a room changes, not because anything has moved, but because the weight inside it has shifted. You feel it when a sound doesn’t land right, when an image sticks even though it wasn’t yours, when the texture of something—tone, structure, format—tells your body to flinch. This is not a revelation. It’s recognition. A shape being traced in reverse.

That’s what I felt when I saw the carousel. This one prompted this essay, but I’ve seen thousands before that are the same.

Not the content. The container. The rhythm of the cards, the choice of gradient, the way the words sit in the centre of each slide like they’re meant to soothe. It’s a familiar cadence, algorithmically trained to gesture at care. But for me, it didn’t hold care. It held pressure—pressure I’ve learned to interpret through the logic of the feed. Not emotional weight, but architectural compression. The kind that happens when something unbearable is reformatted into something acceptable.

I didn’t see “grief,” as it was framed. I saw formatting.

This isn’t a critique of the journalist’s intent. To assume I am writing about intent is to miss the point entirely. There is no intent in a description of structure. I’m not telling you what they meant. I’m telling you what was built. I’m describing the house, not the architect.

Digital platforms force intent into format. The caption says, “here is how people are feeling,” but what it shows is how those feelings have been arranged. It is not a window. It is a diagram.

In this case, a carousel of anonymous messages submitted after a journalist invited followers to share their questions for a psychologist about trauma. There were fifteen slides, all different questions. A neat format. A well-lit room.

But the framing of that exchange—public, curated, aesthetic—betrays a foundational rule in therapeutic dynamics: that safety depends on context, not just consent. That a question asked in private can’t be made safe by removing a name. Especially not in a space like Instagram, where parasociality and platform design replace proximity with performance.

Consent here is a placeholder.

It does not account for how that message will be received—how it will be reshared, reinterpreted, reabsorbed. The question exists in the journalist’s algorithm, not the algorithm of the person who asked it. The content is shaped by the platform’s logic, not the brain that generated the request.

In this context consent is not a contract between the journalist and the giver. It’s not a checkbox. It’s not a shared cup of tea. It’s not intimacy. It’s a gesture made inside an architecture that immediately misinterprets it.

Because the issue isn’t just whether the journalist “has permission” to share. It’s what happens when that permission enters the feed. When the question is no longer a message, but an object.

The slide is the object. It will be screenshotted, reshared, digested by people who were never part of the original exchange. The person who asked it might be watching, might not be. But the question is now in circulation. It is owned by the algorithm. It has become part of the carousel, part of the foggy, ambient churn of “content that matters.”

Consent does not hold shape in that environment.

It cannot account for context loss. It cannot govern interpretation. It cannot protect the person who asked the question from watching strangers try to hold it, twist it, soothe it, celebrate it, dismiss it, relate to it, decide that it’s theirs now.

It’s like liking a photo of yourself that a friend took, thinking it was sweet, only to find that they’ve printed it and taped it to their fridge. But not their own fridge—a stranger’s. A house you’ve never been to. Where people you’ve never met now see your face every day. Admiring it. Commenting. Maybe even meaning well.

But it’s different.

And that difference is not trivial. It’s the difference between safe and exposed. Between gesture and distortion. Between offering something and being entered into circulation.

This is what digital care often misses: that harm isn’t always loud. That violation isn’t always intentional. Sometimes it’s a structure. Sometimes it’s a rhythm. Sometimes it’s a pastel pink carousel that makes your body flinch, even though the words are soft.

Because what’s being violated is not your privacy, or even your dignity.

It’s your pattern. The fragile, private shape you made to survive.

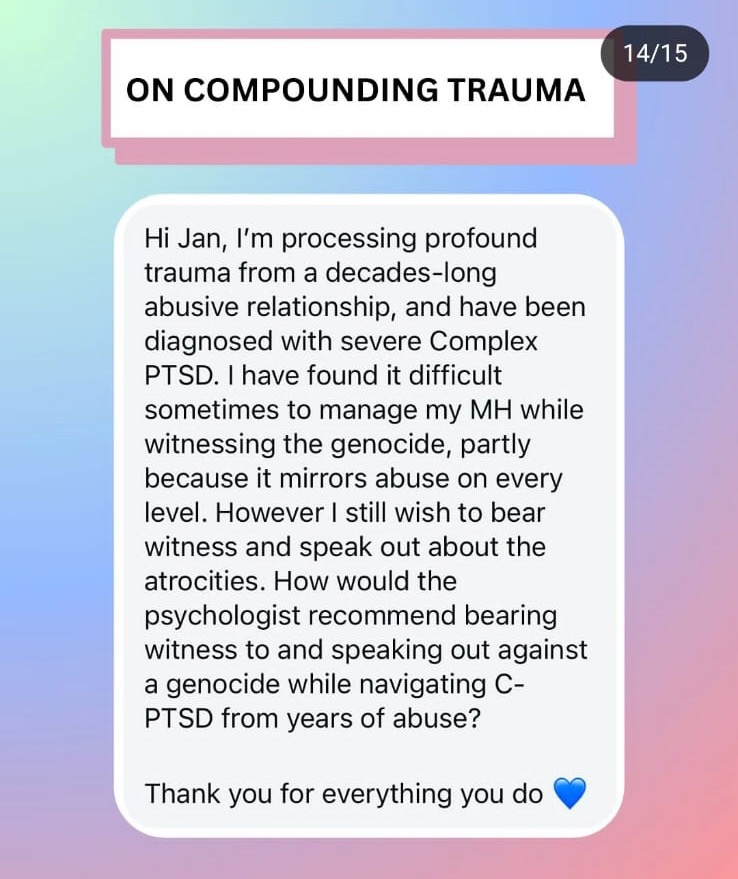

In the midst of these cards, there’s one message that tries to explain itself. That repeats context. That uses cautious, gentle language to indicate safety. It stands out. Not because of what it says, but because of what it knows. This isn’t a fluke. It’s not style. It’s not identity.

The person identifies themselves as someone with CPTSD.

The message is design. It’s structure. It’s cognition.

Trauma-wired brains do not ask for help the way other people do. They do not trust context to hold them. So they embed it. They fold it in. They show you how to read what they are saying as they are saying it, so you don’t miss the shape. So you don’t press the wrong button. So you don’t make the collar fire.

This question will be asked differently in even the slightest different frame of context, but the structure of it will remain the same.

That is not the same thing as asking a question.

This is you showing them a house, and them repeating word for word it back to you so you know that you will understand them,

and then asking “is it safe to come in?”.

It wasn’t the content that set off the reaction. It was the cadence. The way the language curved at the edges. The repetitions. The clarity framed by apology. The instinct to self-regulate as the question was being asked. The tightening of tone, the way it circled itself. I knew what I was reading before I read it. That’s how you know it’s real.

When I saw the message from the person who said they had CPTSD, something changed in my body. Not panic. Not overwhelm. Precision. Like something coming into focus.

Because it’s not the same. It is never the same.

A person with CPTSD doesn’t just ask a question. They construct the safest possible container for it. They regulate you as they speak. They apologise for the possibility of confusion. They offer you shape after shape after shape so that you can choose the one that doesn’t hurt to touch. It’s not performance. It’s not virtue. It’s not style. It’s structure.

That’s why the moment I saw it, I felt something move—protectively, cleanly. Like a hand closing over a lit match before it burned down to skin. I wasn’t responding to pain. I was responding to architecture.

I recognised the material. And I knew what it meant for it to be seen like this: out of context, in the carousel, between gradients, flattened into sameness.

This wasn’t a prompt. It wasn’t content. It was regulation-in-motion. It was someone holding themselves together as they offered the thing. And to be honest, it scared me. Not because it was dangerous—but because it was that familiar.

You don’t react this way to protect the person. You react this way to protect the pattern. Because if you’ve been here—really been here—you know that when people collapse the shape of this kind of speech into mere “expression,” something gets lost that can’t be rebuilt.

You stop recognising yourself in public. You start to doubt whether your way of speaking, of shaping your pain, ever made sense at all. So you guard it. Not to gatekeep. Not to control. But because you know what happens when the map becomes decorative.

When someone takes the blueprint for survival and turns it into a printout for mass interpretation.

This isn’t just a mismatch between platform and person. It’s a structural collapse between container and self, when the self has been built through trauma to function recursively.

People with CPTSD don’t experience the internet as a space. I experience it as a prosthetic. As a cognitive tool that helps your brain do what it was forced to learn: map pressure, identify patterns, trace the shape of threat.

Instagram, like most digital platforms, rewards legibility. It aestheticises affect. It flattens grief into cards, calibrates expression into rhythm, and presents regulation as pastel coherence. This isn’t trauma-informed care. This is platform-compliant pain.

It says: “You can be distressed, but only if you look safe doing it.”

What makes it worse is the way that parasociality gets coded as proximity. When people send messages to a journalist, or reply to a callout, or write “questions for a psychologist,” they aren’t speaking into the void—they’re speaking into someone’s orbit. The questions don’t land in neutral space. They land in an account, a feed, a personality’s branded zone of curated credibility. They land on someone’s page.

And when that person presents those messages—especially without context, in clean, scrolling format—they become the container. Not relationally, not responsibly, but visually, affectively. The slide becomes the space of interpretation, and the audience becomes the witness. But what the interface obscures is the absence of holding. There is no back-end containment. There is no frame behind the frame.

This is the worst inversion of a therapist’s function: someone presents as a conduit, but what they are offering is content. Not space. Not safety. Not coherence. Just content.

And if you have CPTSD—if your entire cognition is built on recursive tracking, on regulation as recognition rather than emotional catharsis—this isn’t just disorienting. It’s annihilating.

When I say I read horror film synopses to calm down, I don’t mean I want to be afraid. I mean: this is what harm looks like, and here is how it resolves. I mean: I am pattern-matching. I am filing. I am indexing the angles of threat.

Because in real life, harm is often shapeless. Chaotic. Boundaryless. But in a horror movie, it’s complete. It has edges. It ends. That is not perversion. That is structure.

So when the algorithm feeds me a carousel of harm, and it lands in a cadence I’ve come to associate with care, my brain doesn’t just absorb it. It reads it as task. As obligation. As signal.

It says: “You’ve seen this. You didn’t stop it. You must understand it.”

And so I spiral. Not out of empathy, but out of logic—because logic, in a trauma-wired system, is what keeps the body alive.

And when that logic breaks—when recognition collapses, when recursion is mistaken for expression, when regulation is read as vulnerability—I lose my map.

This is cognition under pressure.

This is how we survive when our systems are trained to track pain, not as emotion, but as data.

I see this person saying that, explicitly, then lumped into a carousel of grief porn.

When the format fails to account for that structure—when it flattens recursion into softness, or containment into vibe—it doesn’t just miss the point. It destroys the language we used to build ourselves back.

That’s what makes this different. It’s not about vulnerability; this is precision. It’s about the people who are building, inside language, the structures that keep them from disintegrating. And watching those structures be mistaken for tone, for vibe, for aesthetic—that’s what undoes you.

And that, more than pain, is the thing we fear: that one day, our language will stop mapping. That we’ll offer the signal, and no one will hear the code inside it.

I saw someone with CPTSD, who doesn’t respond to pain the way this journalist expects. Who doesn’t seek relief, but pattern. Who doesn’t process chronologically, but recursively. Who is not asking to be helped, but trying to trace the origin of why they were hurt in the first place.

So when I say that seeing that carousel made something in me recoil, I don’t mean I was offended. I mean I was structurally misrecognised. The kind of cognition I live inside—recursive, associative, pressure-mapped—was mistaken for vulnerability. It was taken as a “contribution” to a conversation that isn’t built to hold me.

And that is the harm I am trying to describe.

Not malice. Not exploitation.

Just the quiet violence of a form that cannot hold the people it invites in.

The uncanny thing is that these kinds of “advocates”—especially in digital spheres—aren’t doing harm out of malice, but from a desperate simulation of care learned from an ecosystem that rewards the appearance of it. They believe they are doing something real because it feels like care, looks like care, and receives the response care would. But structurally, it is not protection—it is exposure.

The difference:

- Care without containment is dispersal.

- Protection without understanding is performance.

- Advocacy without scaffolding is collapse.

The trajectory of these actors are often those who have never actually known protection, or are doing so because their own protection is threatened. Who think protecting others will protect them or provide information to repair. This isn’t linear failure. It’s recursive implosion.

The weight gets heavier. The ambiguity gets messier. And they start asking for care through the performance of giving it. And worse—they start believing that martyrdom is the same thing as protection. That to burn out is noble.

This isn’t just unsustainable—it’s dangerous. Because in the vacuum left when that simulation collapses, those who really needed a scaffold of care are left raw, unheld, and sometimes even retraumatised. Especially those who speak in coded, adaptive, trauma-shaped language like this person in the CPTSD slide.

The collapse is often interpreted as: “Even here, I was too much.”

This is not about denying these people's feelings, or mocking their effort. It’s about revealing that the system they’re replicating has already failed them, and in trying to emulate its shape, they are repeating the same logic that harmed them. They do not know what protection is. And the performance of it reveals not strength, but fracture.

There’s a script that unfolds in the minds of people like this journalist—especially those online, especially those who’ve never known true protection but have known the ambient rewards of recognition. It goes something like:

“If I do not carry this, no one will.”

“If I have access to pain, I must use it.”

“If others see me doing this, I must keep doing it—because maybe that means I am good.”

It’s not duty in the sense of care—it’s identification through obligation. The way soldiers are told it’s an honour to go to war. But no one tells them: the war will not end just because you fought. And when you return, you won’t know what to do with peace.

This is what happens to people who aestheticise advocacy. They don’t know that the ability to hold space isn’t the same as holding harm. That trauma isn’t a baton to be passed, or a community resource to be crowdsourced through pastel carousels.

It’s personal. Structural. Recursive. And exposure—especially performative exposure—doesn’t protect anyone. It just looks like protection from far away.

The key thing to note there, that protection from far away is observed, not experienced.

The fantasy of infinite benevolence is just that; fantasy.

The real terrain: containment as care. Not moral containment, not selflessness—but structural clarity. A refusal to posture as saviour, when what’s really needed is a mapmaker.

What is required is a radical reframe of care—not as an open channel, but as a series of boundaries calibrated to capacity. And not in the soft, liberalised sense of “boundaries” as personal limits alone, but in the sense of pathway design. In this frame, care becomes infrastructural. Not “doing what’s good,” but refusing to create conditions that increase the probability of harm, even if the performance looks like help.

This is the opposite of the Instagram carousel logic. This is where “care” is often: invite input, display suffering, perform listening, offer comfort, disappear. However, if you do not know the conditions you’re operating in—your thresholds, your entry/exit routes, your actual risk—then you aren’t creating safety. You’re just rendering harm more ambient. Making it travel further. Turning it into atmosphere.

Care is about choosing conditions in which your presence does not distort the probabilities of harm—and where you are prepared for what you might unleash.

The uncomfortable truth most people performing care online don’t want to confront:

You are already causing harm.

Not because you are bad, but because the conditions within the environment ensure it.

Instagram, by design, creates the illusion of infinite presence and distributable intimacy. When you open the door to one, you imply you are holding space for all. You cannot signal “I receive harm” without also inviting it, even if inadvertently. You do not get to decide who comes through or when, but you are accountable for what they see when they arrive.

The hard truth becomes stone, if you cannot respond to all, and the platform is structured to make all visible, you must assume responsibility for what the act of visibility implies. This is not to generate guilt.

This is naming a structural consequence.

It is never “how do I avoid harming anyone,” but:

What are the consequences I am structurally willing to be accountable for?

Who will I harm by default?

Who will I harm by omission?

What will the harm look like when it refracts through systems I can’t control?

It’s why the language of duty—“I am doing this because I care”—is a trap. It disguises a lack of structural discernment as virtue. It narrows the imagined options to “help or stay silent,” rather than allowing the more honest, more frightening third:

Step out of the arena entirely until you can map it.

Every live wire of ethics, presence, trauma, digital cognition, and the aesthetics of performance under surveillance under this reality becomes exposed. Especially care as a form of performance under structural conditions that do not permit true holding.

The paradox of care is revealed through an environment designed for signal, not containment. Instagram does not permit true containment. It permits broadcasting. So when a person enacts care in that space, what they are actually enacting is the aesthetic of care under visibility constraints—not care itself. This is not a moral failing. It is an infrastructural incompatibility.

And what’s more: the illusion of safety created through care-signalling aesthetics (pastel, even-toned typography, calm language, carousel pacing) inverts threat. The danger is not the thing that looks like danger. It is the thing that appears safe while operating as a false lead. What looks soothing becomes an architecture of false coherence—especially for the CPTSD brain, which detects structure before content.

Deepening, this is where consent becomes an ambient, unfixed object I mentioned. The carousel asks for consent from one party and broadcasts it to 100,000 others. But the effect lands elsewhere—on those who didn’t consent to be witness, whose nervous systems are not operating within the same context, who have no boundary between scrolling and absorbing.

Consent here is not permission—it is weaponised plausibility. It insulates the actor while displacing the impact.

People performing care online often unconsciously inhabit the architecture of those they seek to support. This isn't solidarity—it’s surrogate trauma-locating, a way to grant themselves legitimacy through adjacency. The advocate becomes entangled in the conditions of those they platform. Their protection instinct is not rooted in capacity, but in borrowed identification. And because the platform rewards engagement over discernment, they are compelled to repeat this pattern until collapse.

For the CPTSD-wired mind, witnessing is not empathetic. It is algorithmic pattern consolidation.

When a person posts a carousel of “different” experiences under a unifying theme like “trauma,” the CPTSD brain doesn’t register difference—it registers slippage. This is one pattern. That jolt isn’t felt as metaphor. It is structural, cognitive. It can cause harm because the pattern logic becomes unavoidable, unbreakable, even if the original intention was coherence or comfort.

This is not a one-off misstep by a journalist. This is the inevitable output of a system that equates visibility with reality, and format with safety. The carousel becomes a container for displaced responsibility. People feel held, but what they are held by is not the journalist—it is the illusion of a structural net that does not exist. This is the gap between the affective signalling of care and the infrastructural impossibility of enacting it at scale.

When people feel moved by a carousel like this, they often feel that they are doing something right by feeling moved. They perform their own response as a form of virtue. But this response is induced by structure, not agency. The pink tone, the rhythm, the confessional cadence—all of these are architected to modulate affect. Not truth, not reflection—just affect. And that affect is what people confuse for “alignment.” But:

There is no moral centre to this structure.

There is only output.

And the outputs will always mimic the inputs we incentivise: coherence, legibility, safeness, relatability—never pressure, incoherence, or breakage, which are often the truest markers of actual trauma experience.

You may think I am overreacting. I’m not. This is what it feels like to see something clearly that I have had to learn because of my cognition. To witness, not metabolise. To track the structure that most people call care and recognise it instead as a system for dispersal.

If you think that is overreacting, well, then think about it this way. This is my default sense of reality, of interpretation, and I live with this every single minute of every single day.

So, if that reads as intense, perhaps it should be respected as such?

Because this isn’t a glitch. It is a failure of architecture that cannot hold the people it gestures toward. A system that rewards affective output over structural integrity, and performance over containment. And in that collapse, the people whose cognition was built to survive harm by pattern-recognition—by tracing every contour of pressure in order to stay alive—are asked to endure yet another misreading.

And the deeper harm isn’t that the structure fails to hold. It’s that those who live inside this kind of cognition begin to doubt whether the shapes they built were ever legible at all.

This is not about malice. It’s not about feelings. It’s about the fact that most people are performing care inside a format that was never built for discernment. A format that cannot distinguish between signal and containment. That converts every gesture into again; atmosphere.

So when you say you care, ask: for whom? By what means? Under what conditions?And are you prepared for the consequences, not just of what you hold—but of how?

Because harm isn’t just what happens when things go wrong.It’s also what happens when care is not seen as beholden to structure.

And the ones who built their survival into shapes no one else can read are left watching themselves dissolve in the feed.